Using EVs as Mobile Battery Storage Could Boost Decarbonization

MIT researchers have published a paper on vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology, which allows electric vehicles to return energy to the power grid and provide an eventually renewable power alternative.

Electric and hybrid vehicles accounted for 11 percent of market sales in 2021. Of those sales, 4.8 percent were battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs). The drivers of these cars are familiar with using charging stations while at home or work to give their batteries a full charge.

A battery energy storage system in a garage. Image used courtesy of Adobe Stock

A Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) team has published a paper in the Energy Advances journal that considers the possibility of reversing the charge flow so that when plugged in, cars with full batteries could give back to the power grid.

The hope is that as the number of electric vehicles (EVs) on the road continues to increase rapidly, the vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology could become a cost-effective and mobile energy storage option for a smoother transition into renewable energy.

Jim Owens, the lead author on the MIT paper and a doctoral student at MIT in Chemical Engineering, believes V2G offers the possibility of boosting renewable energy growth and decreasing dependency on stationary storage and always-on generators.

Research Team Calculates Energy Savings from V2G

A challenge in increasing the use of renewable energy sources is the capacity and the limited number of existing energy storage batteries. Solar and wind provide irregular energy production, and the batteries necessary to hold the energy for later use can be large and incredibly expensive. Buildings and homes that use solar panels tend to rely on the power grid for backup.

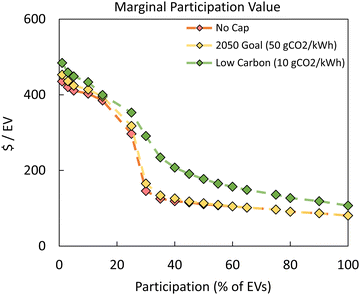

In a case study, the MIT researchers measured the V2G impact on a theoretical New England power system with high EV penetration and tight emissions constraints. With just 13.9 percent of 8 million New England passenger EVs participating in the theoretical study, the team calculated a 14.7-gigawatt (GW) displacement of stationary energy storage, equivalent to $700 million in savings.

This is also equivalent to the expected costs of building new storage capacity. Using V2G technology could displace the need for built storage infrastructure.

A graph from the MIT paper shows the cost savings per percent of EV participation in V2G under varying carbon constraints. Image used courtesy of Energy Advances

EVs as Mobile Power Source Enhance Resiliency

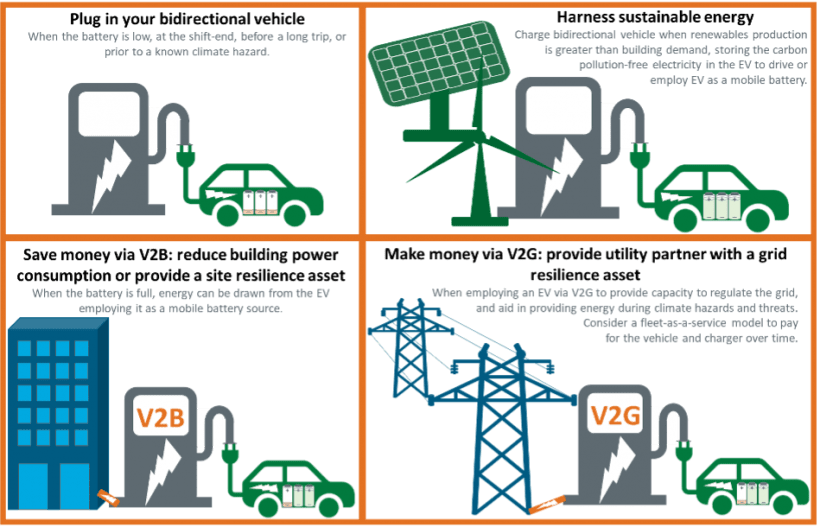

The V2G concept is much more tangible than just a theoretical study in a research paper. In 2013, the University of Delaware joined NRG Energy and the U.S. Department of Energy to start their own eV2g project, being the first to sell electricity from electric vehicles back to the grid. The Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy has voiced its support for what they call Bidirectional Charging and Electric Vehicles for Mobile Storage.

Using vehicle-to-building (V2B) and V2G charging as mobile battery storage can increase resilience and demand response for building and grid infrastructure. As a mobile source, cars can be dispatched to a site before expected outages or in response to unexpected outages. In this case, the use of an EV fleet, rather than participation from consumers, would likely be necessary.

Bidirectional vehicles could offer mobile storage for use with buildings and the power grid. Image used courtesy of Energy.gov

The MIT paper also discusses how V2G technology could assist with times of peak demand. Generally, electricity from the power grid is more expensive at times of peak demand, and using EV batteries could help reduce those costs.

V2G Process Still Has to Attain Net-zero Emissions

The MIT team used two existing modeling tools from the MIT Energy Initiative (MITEI): the Sustainable Energy System Analysis Modeling Environment (SESAME), to project the growth of electricity demand to meet EV growth; and GenX, to model the impact of V2G on grid investments and operations, specifically for electricity generation, storage, and transmission systems.

The modeling incorporated a variety of inputs including different EV participation rates, travel demand for vehicles, costs of conventional and renewable power generation, EV battery costs, and considered the impact of different levels of carbon emission restrictions.

The analysis determined that V2G delivers the greatest value when carbon constraints are the most aggressive, around 10 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt-hour load. V2G support system savings from $183 million to $1.326 billion, depending on EV participation rates ranging from 5 to 80 percent.

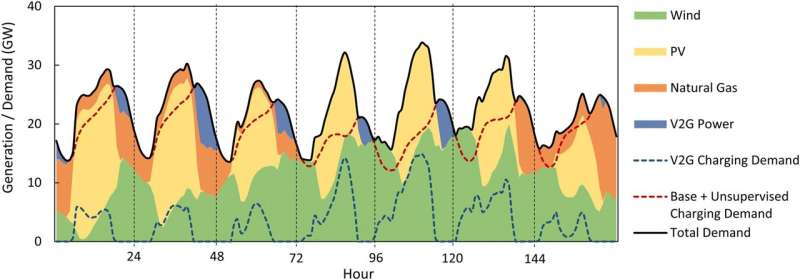

Generation and demand profiles over a week with 50 percent V2G participation. Image used courtesy of Energy Advances

Models that consider the impact of tight carbon restraints are most representative of how the V2G technology could be most beneficial in supporting a decarbonized future.

While the percentage of renewable energy sources powering the U.S. power grid increases every year, nuclear, coal, and natural gas still account for 79 percent of electricity generation as of 2021. This means that unless an EV is plugged into a charging station that is directly powered by a solar panel, the electricity used to charge EVs is coming from fossil fuels.

V2G supports a smoother transition to an all-electric power grid as an economical and long-term energy storage option. Adapting to an all-electric power grid requires ample battery storage to hold onto electricity when not actively produced by solar and wind. Ideally, EVs will be charged using renewable sources and then be able to give back to the power grid in times of low production.

However, until EVs are charged entirely from renewable sources, using their battery power to give back to the grid will not be an inherently net-zero process.

V2G Prospects Point to Promising Future

EV owners are not expected to jump at the opportunity to give their car’s battery power to a utility or power systems operator. Any future software used to facilitate the battery dispatch could be tailored to individual needs to best suit each car owner.

Similar to the adoption of residential solar panels, car owners could be paid for their contribution back to the power grid.

Outside of personal vehicles, Owens is also considering the impact of heavy-duty EVs, such as delivery trucks from Amazon and FedEx that are likely to be early adopters of EVs. These trucks have a regular schedule during the day and are mostly idle overnight, making them appealing to V2G services.Even if fleet and personal vehicles choose not to participate round-the-clock, expanding access to V2G technology could be impactful in times including energy blackouts, hot-day congestion, and peak demand putting stress on transmission lines.